Lesson 3: Numerical systems, CLI commands, diff and patch

2024-10-23

Homework take-aways

cat test.txt will print the content of test.txt to the screen.

However if you do cat by itself, you seem to be “stuck”.

Things to try: CTRL-C (break), CTRL- (really break), CTRL-D (exit).

Sometimes CTRL-D on newline.

However, don’t press it twice, or you’ll exit your shell ;)

Note

Mac users: This is the one time when CTRL-C is also CTRL-C.

Warning

Windows users: don’t use CTRL-C for copying in gitbash.

Lesson 3

- Numeral systems: binary, octal, decimal, hexadecimal

- CLI commands: pipe, redirect, how programs fit together (& terminal)

- Diff and Patch

Sizing things in computers

- Everything is counted in bytes

- kB, MB, GB, TB (note: steps of 1024)

- A byte is 8 bit, or a number between 0-255

- Sometimes better to think of a byte as a letter out of a alphabet with 256 letters

- (A=0, B=1, etc)

- So 1kB = 1024 bytes; like a text of 1024 “256-letters”

- Other times, multiple bytes work together to make a number (e.g. 4 bytes can represent a number between 0 and 4,294,967,296 (or -2,147,483,647 and 2,147,483,648, or float)

- That is why we now need to talk about number systems

Numeral systems

If you thought that at least numbers were something you could count on being simple….

You’re wrong!!

Numeral systems

- Decimal (base 10)

- Binary (base 2)

- Hexadecimal (base 16)

- Others

Decimal (base 10):

Binary (base 2)

Written as 0b.....

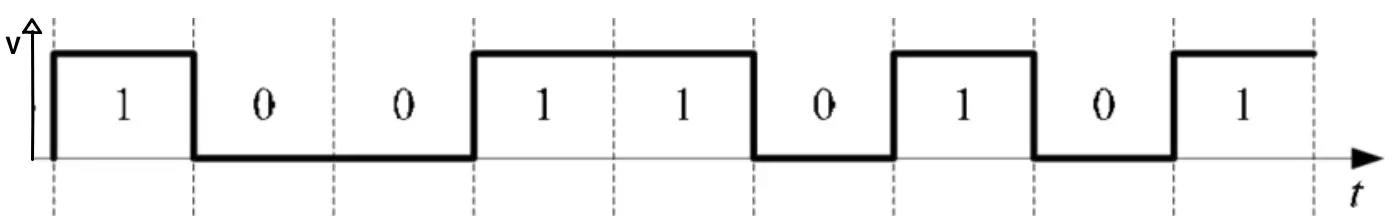

A single 1 or 0 is called a bit. 8 bits is a byte:

There are 10 types of people in the world: those who understand binary, and those who don’t.

Endianness

byte

Please decode what byte is in the signal above

Hexadecimal (hex; base 16)

Written as 0x..... We need characters for the numbers 10-15: A=10, B=11, C=12, D=13, E=14, F=15. Both uppercase and lowercase used

Two hex-digits are one byte (16 * 16 = 256)

lesser systems

Octal (base 8)

Written as 0o..... or 0....

Only used in specific contexts

Base 64

Uses symbols 0-9a-zA-Z (10 + 26 + 26 = 62) and two extra (often + and \).

Used to display binary data in “printable symbols”

Side note: other non-computer bases

- Base 10 comes from “counting on one’s fingers”

- Base 12 (duodecimal) minor and speculative usage, foot-inch, dozen-gross, months in year, 12 hours in a day (and 12 in a night).

- Base 20 (vigesimal) Mayans, some early European systems

- Base 60 (sexagesimal) used by Babylonians and still in use for time-keeping / angular positioning:

UK until 1971: 4 farthing = 1 penny, 12 pence = 1 shilling, 20 shilling = £1

Note that base 12 and base 60 nice for mathematical reasons.

Why all these bases / when to use which

- Decimal is just because people are used to it

- Computers work with bits and bytes (= 8 bits), which have 2 and \(2^8=256\) values. So it’s nice if your number system uses powers of 2 or powers of 256.

- Binary has \(2^1\) values per digit (so 1 bit)

- Octal has \(2^3=8\) values per digit (so 3 bits)

- Hexadecimal has \(2^4=16\) values per digit (so 4 bits = 1 nibble, 2 hex-digits = 1 byte)

- Base 64 has \(2^6=64\) values per digit (so 4 digits = 24 bits = 3 bytes)

Generally things will have a prefix:

- No prefix: decimal

0b...: binary (eg.0b10101010)0o....: octal. Sometimes also (annoyingly) just0.... So0123 !== 123(0123 == 0o123 == ...)0x...hexadecimal. Often written in groups of two:0xFF A0 01 00 45 76 7E 0Eto represent bytes.

Sometimes, you can only know from context:

- If things mix upper and lowercase letters and numbers, good chance it’s base64

- If things mix numbers and letters A-F (either uppercase or lowercase but not both) it’s usually hexadecimal

- Some commandline programs (like

chmodalways expect octal numbers) - Some domains always use hexadecimal (e.g. in HTML (and R), color grey is

rgb(127, 127, 127) == #7F7F7F. So#111111 !== rgb(11, 11, 11)

CLI programs

Connect them

(like audio equipment / signal processors)

Default filedescriptors

stdin: standard input (to a program). Connected to terminal (what you type) by default, if not piped in from somewhere elsestdout: standard output (from a program). By default print to terminal.stderr: standard error (from a program). Here the program will send warnings and error messages. By default connected to the terminal

Redirections

|pipe character, connects thestdoutof the previous program to thestdinof the next program.>sends thestdoutof the previous program to a file>>appends thestdoutof the previous program to a file<uses the content of a file asstdinto the previous program

Some commands

These commands all work on stdin, but can also take a filename (or multiple)

cat– print contenttr abc def– replace everyawithd, everybwithe, etc.wc -l– count lineswc -c– count charactersgrep Raven– only show lines with the word “Raven”grep -v Raven– only show lines without the word “Raven”grep -n Raven–-nadds line numbershead -n 10/tail -n 10– show first / last 10 linescut -d ' ' -f 2-3– show words 2 and 3 for each line

e.g. cat test.txt | grep hello | tr he ba

Hands-on

For this hands-on work, you need some files. In order to get the files, we will clone a git repo from GitHub:

# make sure you're in a directory where you want to make a subdir "raven"

git clone --branch lesson3 https://github.com/reinhrst/raven

cd ravenNOTE: Even though we use a git repo to download the files, the things we do in this playtime are NOT using git.

In the raven directory there are different versions of the poem by E.A.Poe. For now we focus on original.txt.

- Print the poem

- How many lines does it have?

- Print only the lines with

raven. Is this what you expected? - How many lines are there without an

ain them. - Print the lines with both

birdandfancyin them - Now the same, but only the first line

- Now the same, but with line numbers

- Can you make the poem about a Tiger?

Line endings

One thing we have to talk about is line endings.

For normal text (in English alphabet, no accents or emojis etc) each character is 1 byte:

- “a” = 0x61, “b” = 0x62, “c” = 0x63, …, z = “0x7a”

- “A” = 0x41, “B” = 0x42, “C” = 0x43, …, Z = “0x5a”

- “0” = 0x30, “1” = 0x31, … “9” = 0x39

See the ASCII table for the full table.

There are special characters here as well:

- 0x20 = SPACE (if you ever noticed that in a URL spaces are (sometimes) represented as

%20, now you know) - 0x0a = LINE FEED / NEWLINE (also written as

\n) - 0x0d = CARRIAGE RETURN (CR; also written as

\ror^M)

Windows and the rest of the world disagree on what should be on the end of a line of text:

- Windows wants all lines to end in

\r\n(or 0x0d 0a, or CR LF) - The rest of the world wants lines to end in only

\n(0x0a, or LF) - (old macs actually had only

\rat the end of a line, but this was changed in 2001, now they use\n)

Most editors on both Windows and Linux/Mac can these days deal with both types of line endings, however some cannot.

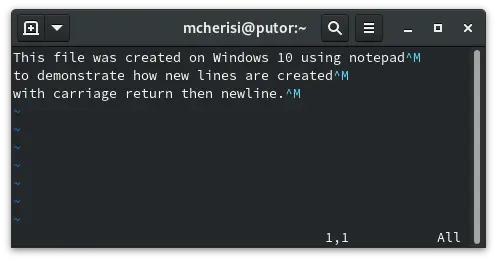

If you open a file with windows line-endings in an editor without support, every line seems to end in ^M before the newline,

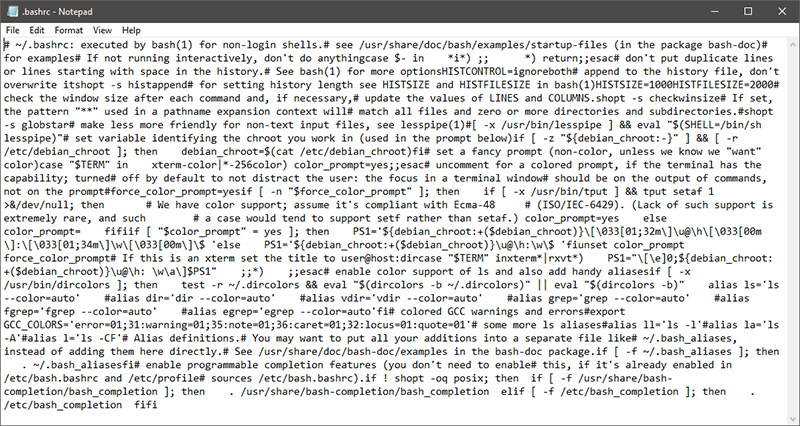

If you open a file with unix line-endings in a (windows) editor without support, all newlines seem to have disappeared (sometimes replaced by some character).

Carriage returns on linux

A file with windows line-endings opened in a mac editor. The ^M is actually a single byte (0x0d, CR).

Unix line endings on notepad

A file with unix line endings opened in notepad (pre-2018; these days notepad does the right thing)

These days most editors can deal with both types of enters, however some may always save files with a certain kind of line ending.

This is a major issue for tools like git; if you open a text file in your editor, change one word, and save it with all line endings changed, diff will think that every line has changed`.

The solution is some magic: By default, on Windows, git converts all line endings to \r\n on checkout (we will get to this term next week, it means taking a version from the repository and presenting it in the working directory), and convert the line endings back to \n on commit.

Tools like diff and patch also use magic, but…

sometimes with magic, things go wrong…

If you ever find yourself in trouble:

dos2unix filename.txtconverts window line endings to unix line endingsunix2dos filename.txtconverts unix line endings to windows line endings

These programs are idempotent; this means that if you run dos2unix on a file that already has unix line endings, it will do nothing (so there is no harm in trying).

You can use the file program to find out if a file has windows line endings:

diff & patch

Understanding git means understanding diff and patch, which do most of the interesting work.

diff file1 file2shows the difference between 2 filesdiff --color --unified file1 file2shows the difference between 2 files in better formatpatch orginal patchfile -o -applies the patchfile (result of diff) to original

Note

- To save the diff to a file, make sure to exclude the

--coloroption – text files cannot have colour. - Windows users will have to run

diff --unified --strip-trailing-cr file1 file2to create a patch file with the correct line endings. Note that this is only for this week, as soon as we start withgitit should not be a problem anymore. - Alternatively, Windows users can run

diff --unified file1 file2 > patchfile.patchand thendos2unix patchfile.patch

Let’s use diff so we understand how it works

- Look at the contents of

orginal.txt - Now look at the contents of

orginal2.txt - Determine the differences between the two files.

For the modern?.txt files, assume the following. modern.txt is the original file. Then 4 different people made some changes (independent of each other) leading to modern2.txt, modern3.txt, modern4.txt and modern5.txt.

- look at the differences between

modern.txtand each ofmodern?.txt - make a patchfile for

modern.txttomodern2.txt(how can we writestdoutto a file?) - apply this to

modern3.txt. Save the result inmodern23.txt. - now add the changes of

modern4.txtto itmodern234.txt - now make

modern2345.txt, adding the changes ofmodern5.txt. Did it work? Why not?