Playtime 7

2024-11-27

Step 1: fix the default git pull behaviour

For those on GitBash (=windows), it turns out that during installation of GitBash it asks if you want default pull behaviour to be merge or rebase. The default option (which I told you guys to choose when we did this in week 1) is fast-forward or if not possible merge.

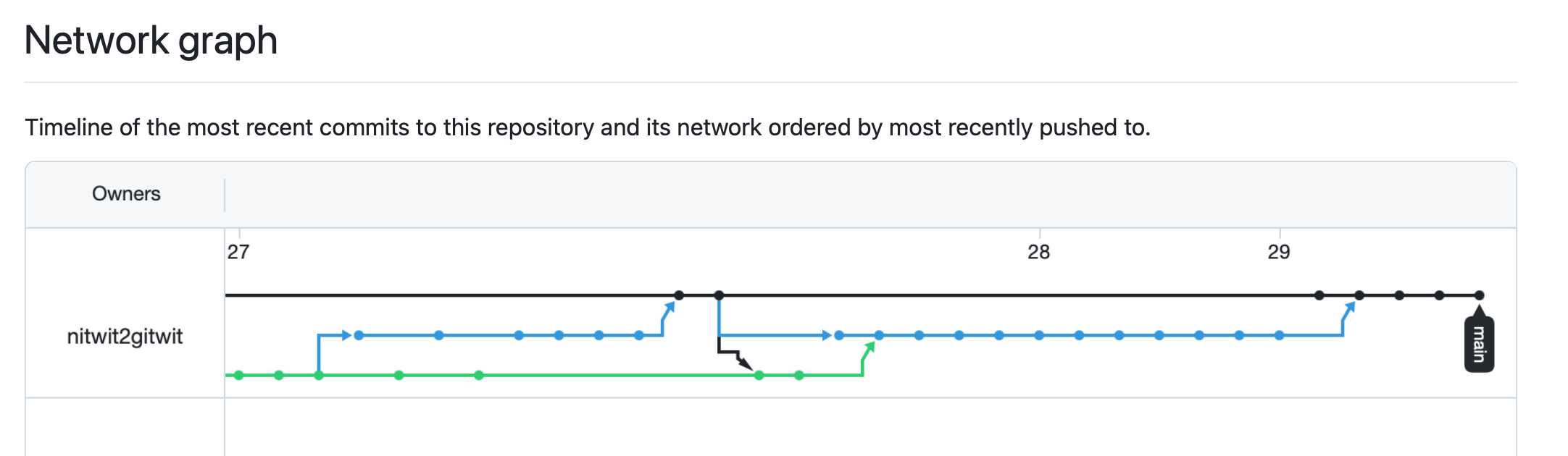

This leads to quite complex splitting and merging in the main branch, and lots of merge commits, and although this is not wrong (some repositories may even demand this behaviour), it makes things hard to follow for beginning gitters, and hard to explain for the teacher (or even to understand :)).

Our current convoluted network graph with lost of branches and merges

In order to fix this, I would advise that everyone on GitBash to run:

This tells that from now on we want to use rebase for pull on all repositories (unless you overwrite this for a certain repository).

What you will notice is that next time you do a git pull when your branch has diverged from GitHub is that it says something like:

rather than telling you to write the commit message for the merge commit.

To do coming weeks

From this week on, if you want to reach out to me about the course, please post a bug on https://github.com/reinhrst/nitwit2gitwit, for things including, but not limited to:

- Being stuck with an exercise

- Suggesting a topic to discuss in the coming weeks (I have some ideas but there might be better suggestions out there).

- Reporting an error in the slides / etc.

For the coming two weeks there is one big exercise, which is one page to the right from here. You will be experiencing how to make and resolve some conflicts.

In addition the goal for the coming two weeks is to every day to something; it can be making and pushing a commit, it can be writing or responding to an issue on GitHub, it can be playing to get some conflicts. Ideally you would achieve three interactions a day on average.

(Note that we can all help each other here; if one person creates an issue, the other person is more likely to want to finish it.)

Cheatsheet for some of the things we did in class

If you want to assign an issue to someone, you can do so from the interface. Please note that it’s generally considered very impolite to do this without the person’s approval!.

I don’t care what you do in this class (and by all means assign away!), if you want you issue that you post on someone’s real repository, don’t assign it. If they don’t respond after a week or two (or you would like a particular person’s attention on an issue), you can gently nudge them by using @username in the text.

Thy this @username in your tickets here!

In many teams it’s good practice that if you start working on an issue, you assign the issue to yourself. This way you avoid two people working on the same issue.

When you fix an issue, you can use the following in your commit message “Fixes #7”, and when this commit is pushed/merged into GitHub main it will automatically close issue #7 (the whole list of magic words is here). This (as well as any other actions on an issue) will send a notification to the person who created the issue (so that e.g. they can check if your fix works for them).

As good practice I tend to copy the issue title in this commit message too, so something like: “Fixes #7: No image is showing on the Cheese Fondue recipe”. This way when people look at the commmit message (e.g. in git log or in git blame) they know directly what issue #7 is (even if they are not on GitHub).

Putting “#7” in your commit message will automatically link it to issue #7. This is useful when looking at issue #7 (you see the commits that relate to the issue), but also very useful later, when looking at the history. When you look at some code and you wonder “Why &*@*# did the author do things this way”, and you look at git blame and see that it refers to issue #7, you can read up on that and at least understand what problem the author was trying to solve.

How to create conflicts

Since you guys already want to start playing a bit with conflicts, I decided to write something quick on this.

Conflicts can only ever happen when doing a merge or rebase (including using pull which does these things under water). If you want to play with conflicts, the easiest is to make some branches (much easier that pushing and pulling to GitHub).

Mini cheatsheet

| command | action |

|---|---|

git checkout -b BRANCHNAME |

creates a branch and switches to this branch |

git checkout BRANCHNAME |

switches to an existing branch |

git merge BRANCHNAME |

merges BRANCHNAME into your current branch |

git rebase BRANCHNAME |

rebases the current branch on BRANCHNAME, so BRANCHNAME will be an ancestor of the current branch. |

So a

git pull --no-rebaseis actuallygit fetch && git merge origin/main(assuming you’re on themainbranch now.git pull --rebaseisgit fetch && git rebase origin/main

If you need to brush up on merge vs rebase, look at the start or lesson 7 slides.

By default if you make branches (e.g in the recipes-2024 repo) the branches will be local, and not go to GitHub. If you try to push them, you get a message:

fatal: The current branch test has no upstream branch.

To push the current branch and set the remote as upstream, use

git push --set-upstream origin BRANCHNAME

To have this happen automatically for branches without a tracking

upstream, see 'push.autoSetupRemote' in 'git help config'.if you do want to push the branch to GitHub (no need to test conflicts, but feel free to play with this), do git push --set-upstream origin BRANCHNAME (obviously replacing BRANCHNAME with the name of the branch on GitHub (which normally will be the same as your local branch name).

Often teams/repository have rules, that if you want to push your branch to GitHub it should be called something like username/branchname, to avoid the situation where 10 people will all want to create and push a branch called test (but in this repository, do what you want!).

What creates a conflict

You get a conflict when two branches have diverging information, and git does not know how to combine/fix it.

For text-files (code, markdown, quarto, csv), generally git will only have a conflict when the two branches edit the same line in different ways.

For non-text files (images, Word documents, etc), there will be a conflict as soon as both branches edit the file.

You will also get a conflict when one branch edits the file, and the other one deletes it.

In the rest of these pages, we will try to make an example of each conflict (and show you how to fix it).

start

We need a new repo, with a main branch.

We will add and commit a single file (shopping.md) which is our shopping list:

Commit this.

no conflict

We start with a situation where there is no conflict to show how merge works. Don’t just copy-paste the commands below, understand them (since in the next exercises you have to do it yourself). If you don’t remember what a commands means, just copy-paste it into chatgpt, it will tell you.

$ git checkout -b branch1

Switched to a new branch 'branch1'

$ echo " - 3 mid-sized tomatoes" >> shopping.md

$ git diff

diff --git a/shopping.md b/shopping.md

index b5df970..43a4ec3 100644

--- a/shopping.md

+++ b/shopping.md

@@ -2,3 +2,4 @@

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- 2 bottles of milk

+ - 3 mid-sized tomatoes

# Shortcut: "git commit -a" is the same as first "git add ." and then "git commit"

$ git commit -a -m "add tomatoes"

[branch1 cfebe3a] add tomatoes

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

$ git checkout main

Switched to branch 'main'

# now edit your shopping list to get 12 eggs (note that this list does not have tomatoes)

$ nano shopping.md

$ git diff

diff --git a/shopping.md b/shopping.md

index b5df970..bc9d7e3 100644

--- a/shopping.md

+++ b/shopping.md

@@ -1,4 +1,4 @@

- - 10 eggs

+ - 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- 2 bottles of milk

$ git commit -a -m "we also need eggs for breakfast tomorrow"

[main 239e8f3] we also need eggs for breakfast tomorrow

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

# now the magic

$ git merge branch1

Auto-merging shopping.md

Merge made by the 'ort' strategy.

shopping.md | 1 +

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+)

$ cat shopping.md

- 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- 2 bottles of milk

- 3 mid-sized tomatoes

# Note both the 12 eggs and the tomatoes --> merge was a success

# Finally remove the branch1 because it's merged

$ git branch -d branch1

Deleted branch branch (was cfebe3a).

# And see how nice diverge and merge in the log

$ git log --graph

* commit 4c3e7c842f6922a638884c49fa961faff8955a3b (HEAD -> main)

|\ Merge: 239e8f3 cfebe3a

| | Author: Claude <github@claude.nl>

| | Date: Thu Nov 28 13:50:41 2024 +0100

| |

| | Merge branch 'branch1'

| |

| * commit cfebe3acf47ed7afa3370bdbbafa5078082885dd

| | Author: Claude <github@claude.nl>

| | Date: Thu Nov 28 13:42:21 2024 +0100

| |

| | add tomatoes

| |

* | commit 239e8f3130aa08656faf19ed577587d6b6be6c07

|/ Author: Claude <github@claude.nl>

| Date: Thu Nov 28 13:49:55 2024 +0100

|

| we also need eggs for breakfast tomorrow

|

* commit 7e463563137bb8a03866d63cc3cb53ac0c5ca444

Author: Claude <github@claude.nl>

Date: Thu Nov 28 13:39:58 2024 +0100

shopping listConflict: same line edited in both branches

- We start with the repo we had at the end of the last exercise (so 12 eggs, and apples)

- Again make a new branch (you can reuse the name

branch1since we deleted it - Now in the new branch edit the “milk” line so that we have 4 bottles of milk and commit

- Go back to the

mainbranch and edit the file, change the milk line to read “2 large bottles of milk”. - Commit this too

- Now it’s time to merge and see what happens.

- When the merge fails, you have to open the file (with

nanoor RStudio or what you want) and decide what the correct solution is). Then add the file and commit. You will see that there is already a commit message filled in (but you can add stuff).

Note

If you think about it, it’s actually super nice that git doesn’t automatically try to merge this. Imagine that some uncle comes over to the house, and you know he likes milk. So you change “2 bottles of milk” to “4 bottles of milk”. However your partner also knows this and changes it to “2 large bottles”. Probably you wouldn’t want to end up with 4 large bottles (which would be the automatic merge).

$ cat shopping.md

- 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- 2 bottles of milk

- 3 mid-sized tomatoes

$ git status

On branch main

nothing to commit, working tree clean

$ git checkout -b branch1

Switched to a new branch 'branch1'

$ nano shopping.md

$ git diff

diff --git a/shopping.md b/shopping.md

index f2a739c..8725997 100644

--- a/shopping.md

+++ b/shopping.md

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

- 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- - 2 bottles of milk

+ - 4 bottles of milk

- 3 mid-sized tomatoes

$ git commit -a -m "Uncle John is coming over and we need more milk"

[branch1 d899072] Uncle John is coming over and we need more milk

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

$ git checkout main

Switched to branch 'main'

$ nano shopping.md

$ git diff

diff --git a/shopping.md b/shopping.md

index f2a739c..8725997 100644

--- a/shopping.md

+++ b/shopping.md

@@ -1,5 +1,5 @@

- 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- - 2 bottles of milk

+ - 4 bottles of milk

- 3 mid-sized tomatoes

# This time using first `git add .` and then `git commit` without `-a`

# just to show that either will work

$ git add .

$ git commit -m "Uncle John is coming over and we need more milk"

[main 48a889b] Uncle John is coming over and we need more milk

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

$ git merge branch1

Auto-merging shopping.md

CONFLICT (content): Merge conflict in shopping.md

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

$ git status

On branch main

You have unmerged paths.

(fix conflicts and run "git commit")

(use "git merge --abort" to abort the merge)

Unmerged paths:

(use "git add <file>..." to mark resolution)

both modified: shopping.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

# so git status shows us which file is the problem (since your repo may have more

# than one file) and what the solution is.

# cat shopping.md

- 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

<<<<<<< HEAD

- 2 large bottles of milk

=======

- 4 bottles of milk

>>>>>>> branch1

- 3 mid-sized tomatoes

# So our shopping file now contains <<<<< and ===== and >>>>>.

# These are called "conflict markers".

# <<<<<< HEAD means this section is the HEAD (HEAD meaning "where we are now" in git

# >>>>>> branch1 means that the previous section was what branch 1 contains.

# ========= is where one section starts and the other ends

# At this time, you have to manually decide what to do.

# Assuming that the other edit was made by someone else, you have to figure out what

# that person wanted to do (were they fixing the same proble m (uncle John coming)

# or was there another reason that even more milk is needed.

# Look at the commit message, or else look at who committed it and just ask them.

# In this case, let's edit the file so that only "4 bottles of milk" is left

# (so removing 4 lines, including the conflict markers.

# NOTE: in real life, always make sure you check the rest of the file for conflict markers.

# There might be multiple places where there is a conflict in a single file!

$ nano shopping.md

$ cat shopping.md

- 12 eggs

- 500g flour

- 500g sugar

- 4 bottles of milk

- 3 mid-sized tomatoes

$ git diff

diff --cc shopping.md

index 2a65723,8725997..0000000

--- a/shopping.md

+++ b/shopping.md

# What happened here? git diff can only show the difference between two versions,

# usually the version you are working on and the latest commit (HEAD).

# In this case it would have to somehow show the diff between your version,

# the version is main, and the version in branch1, and it cannot.

# Therefore it just says "there are differences but I cannot show you what"

$ git add shopping.md

$ git commit

[main 83c4829] Merge branch 'branch1'

# Let's clean up our branch

$ git branch -d branch1Conflict because edited file removed

- We continue where we left off (although it doesn’t really matter much).

- Make a new branch

- In the branch, change “500g sugar” for “750g sugar”, and commit

- Now on main, remove the shopping-list (

git rm FILENAME) and then commit. - Now merge and let’s see what happens. Solve the problem and commit.

Note

It’s interesting that actually these conflict rules work very well for both a shopping list and for code.

In case of our shopping list, it makes sense that if I delete the shopping list (e.g. because I did the shopping, or likewise because the party was cancelled), and my partner changes something on that list (that I did not see yet), the list cannot just be removed. In this case 250g of sugar was added; maybe it’s not needed because I bought 1kg (or it was for the same, cancelled, party). On the other hand, maybe it is now necessary to get 250g of sugar. git cannot know this and therefore leaves the solution to you.

Likewise with code the same rules apply. Imagine that you remove 1 file from your project because it’s not being used anymore. However someone else just edited that file and added a function that is being used everywhere. In that case, it’s nice that git helps you by not just deleting the file.

That this system is not fool-proof can be understood by the following situation. You delete a file after you carefully check that it’s not being used anywhere anymore. However someone else just added some code somewhere else that uses this file again. In this case git will not give you a conflict.

Therefore it’s always important to test that your merged code works as intended (either manually test it, or have automatic tests).

$ git checkout -b branch1

Switched to a new branch 'branch1'

$ nvim shopping.md

$ git commit -am "more sugar is needed for the pie"

[branch1 17b8d24] more sugar is needed for the pie

1 file changed, 1 insertion(+), 1 deletion(-)

$ git checkout main

Switched to branch 'main'

$ git rm shopping.md

rm 'shopping.md'

$ git commit -m "Shopping is done"

[main 0bc19d5] Shopping is done

1 file changed, 5 deletions(-)

delete mode 100644 shopping.md

$ git merge branch1

CONFLICT (modify/delete): shopping.md deleted in HEAD and modified in branch1. Version branch1 of shopping.md left in tree.

Automatic merge failed; fix conflicts and then commit the result.

$ git status

On branch main

You have unmerged paths.

(fix conflicts and run "git commit")

(use "git merge --abort" to abort the merge)

Unmerged paths:

(use "git add/rm <file>..." as appropriate to mark resolution)

deleted by us: shopping.md

no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

# So that is cool. It tells that "shopping.md" was "deleted by us".

# This means it was deleted in the branch that you are trying to merge into.

# From a `git pull` perspective this would make even more sense; then it would mean it's

# deleted by us (on this computer) as opposed to "deleted by them" (if it was deleted in the branch

that you're trying to merge, or, in the GitHub case, on GitHub).

# The message also tells us that it left the version of the file that was in branch1.

# However it does not just want to leave that one, therefore it flagged it as a conflict and leaves it to you what to do with it.

# Option 1: edit the file (with nano) to what you want it to be, then "git add" and "git commit"

# Option 2: "git rm" the file if you don't need it anymore, and commit

# Option 3: do "git merge --abort". It basically means "I changed my mind, I don't want this merge anymore".

$ nano shopping.md

$ git add shopping.md

$ git commit

$ git branch -d branch1Now rebase

It would be interesting (if you have more tiume) to now do a git log --graph and see all the branching and rejoining that we made.

Also do the exercises again (or just continue in your repo) but now do git rebase instead of git merge and see how it influences the graph.

You can also do all these things with extra branches, or even remote branches on GitHub. But the basics will always be this!